Phytochemistry

Phytochemistry is the study of plant-derived chemicals, also named - the phytochemicals.

Those who are researching phytochemistry seek to identify the structures of a large number of secondary metabolic compounds found in plants, the roles of these compounds in human and plant biology, and their biosynthesis.

For numerous factors, plants synthesize phytochemicals one example of which is to defend themselves from insect attacks and plant diseases.

Phytochemicals in food plants are often used in human biology and have health benefits in many cases. The substances found in plants are of various types, but most are in four main biochemical classes: alkaloids, glycosides, polyphenols, and terpenes.

The Phytochemistry of Cherokee Aromatic Medicinal Plants

William N. Setzer 1,2

1 Department of Chemistry, University of Alabama in Huntsville, Huntsville, AL 35899, USA;

wsetzer@chemistry.uah.edu; Tel.: +1-256-824-6519

2 Aromatic Plant Research Center, 230 N 1200 E, Suite 102, Lehi, UT 84043, USA

Received: 25 October 2018; Accepted: 8 November 2018; Published: 12 November 2018

Introduction

Natural products have been an important source of medicinal agents throughout history and

modern medicine continues to rely on traditional knowledge for treatment of human maladies [1].

Traditional medicines such as Traditional Chinese Medicine [2], Ayurvedic [3], and medicinal plants

from Latin America [4] have proven to be rich resources of biologically active compounds and potential

new drugs. Several plant-derived drugs are in use today, including, for example, vinblastine (from

Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don, used to treat childhood leukemia); paclitaxel (from Taxus brevifolia Nutt., used to treat ovarian cancer); morphine (from Papaver somniferum L., used to treat pain); and quinine (from Cinchona spp., used to treat malaria) [5]. Not only are phytochemicals useful medicines in their own right, but compounds derived from them or inspired by them have become useful medicines [6,7].

For example, Artemisia annua L., a plant originally used in Traditional Chinese Medicine to treat fever,

is the source of artemisinin, a clinically-useful antimalarial sesquiterpenoid [8]; the antihypertensive

drug reserpine, isolated from the roots of Rauvolfia serpentina (L.) Benth. ex Kurz., has been used

in Ayurveda to treat insanity, epilepsy, insomnia, hysteria, eclampsia, as well as hypertension [9];

Dysphania ambrosioides (L.) Mosyakin and Clemants (syn. Chenopodium ambrosioides L.) is used in several Latin American cultures as an internal anthelmintic and external antiparasitic [4] and has shown

promise for treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis [10].

The biological activity of D. ambrosioides has been attributed to the monoterpenoid endoperoxide ascaridole.

Unfortunately, much of the traditional medicine knowledge of Native North American peoples

has been lost due to population decimation and displacement from their native lands by European

conquerors (see, for example: [11–14]). Nevertheless, there are still some remaining sources of information about Native American ethnobotany [15,16]. In addition, there are several sources of

Cherokee ethnobotany [17–22].

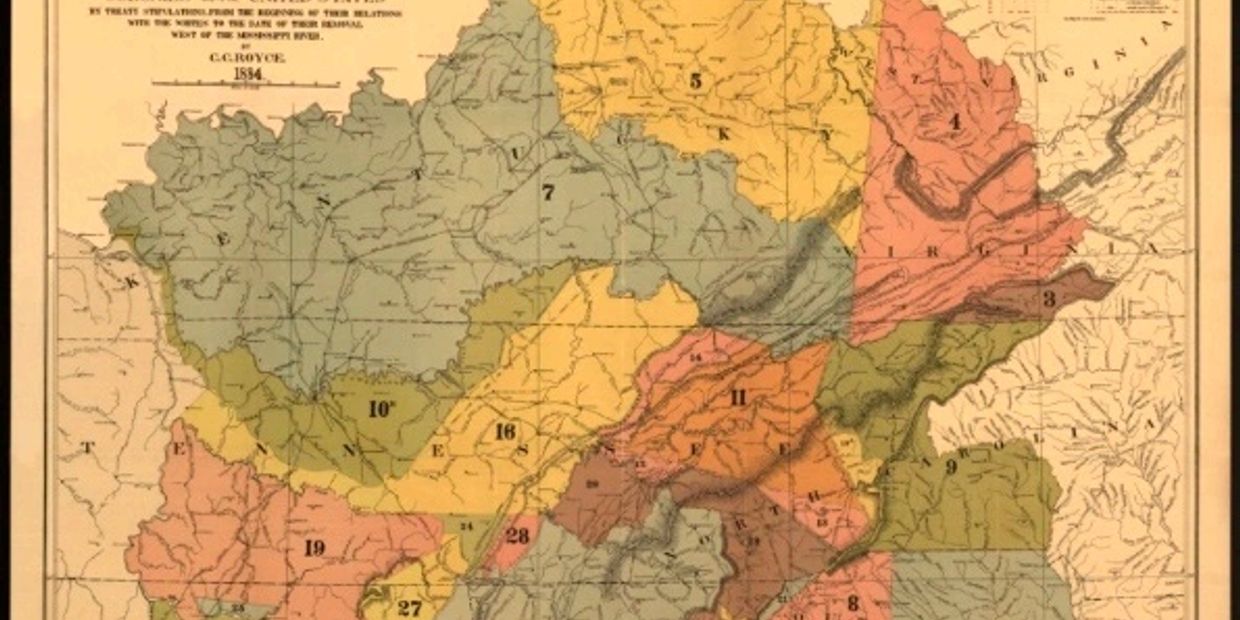

The Cherokee Native Americans are a tribe of Iroquoian-language people who lived in the

southern part of the Appalachian Mountain region in present-day northern Georgia, eastern Tennessee, and western North Carolina and South Carolina at the time of European contact [13] (Figure 1A).

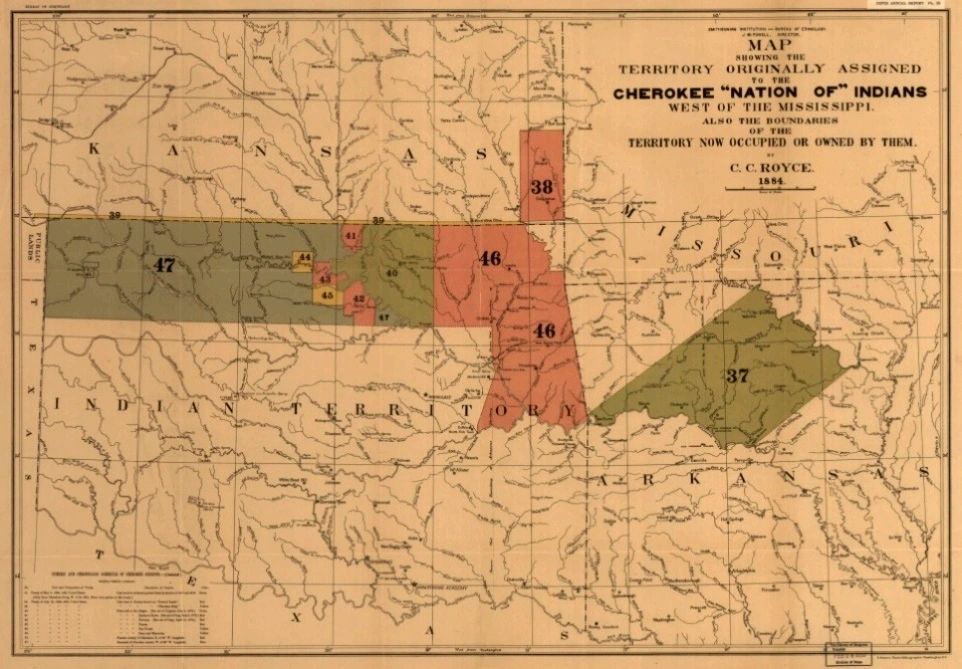

During and after the American Revolution, Cherokee wars with European settlers resulted in the

surrender of vast amounts of territory. Gold was discovered on Cherokee land in north Georgia

and the Treaty of New Echota (1835) ceded all Cherokee land east of the Mississippi River to the

United States. Congress passed the Indian Removal Act in 1830, and the forced eviction of as many as

16,000 Cherokee took place during the fall and winter of 1838–1839 to a new territory in north-eastern Oklahoma (Fibure 1B). During this “Trail of Tears”, an estimated one-fourth of the Cherokee died.

However, at the time of the removal, a few hundred Cherokee successfully escaped to the mountains

of western North Carolina, forming what is now the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians.

In this review, I have consulted the ethnobotanical sources for plants used in Cherokee

traditional medicine [15–24] and I have carried out a literature search using Google Scholar, PubMed,

ResearchGate, and Science Direct for phytochemical analyses on the plant species. Note that in many

instances, the phytochemistry was determined by plants not collected in the south-eastern United

States; many of the species have been introduced to other parts of the world and some species are native to other continents besides North America. The phytochemistry, therefore, may be affected by the different geographical and climatic conditions [25]. Sources reporting the phytochemical constituents, regardless of geographical origin, have been included.

Medicines 2018, 5, x FOR PEER REVIEW 2 of 90

Unfortunately, much of the traditional medicine knowledge of Native North American peoples

has been lost due to population decimation and displacement from their native lands by European

conquerors (see, for example: [11–14]). Nevertheless, there are still some remaining sources of

information about Native American ethnobotany [15,16]. In addition, there are several sources of

Cherokee ethnobotany [17–22].

The Cherokee Native Americans are a tribe of Iroquoian-language people who lived in the

southern part of the Appalachian Mountain region in present-day northern Georgia, eastern

Tennessee, and western North Carolina and South Carolina at the time of European contact [13]

(Figure 1A). During and after the American Revolution, Cherokee wars with European settlers

resulted in the surrender of vast amounts of territory. Gold was discovered on Cherokee land in north

Georgia and the Treaty of New Echota (1835) ceded all Cherokee land east of the Mississippi River to

the United States. Congress passed the Indian Removal Act in 1830, and the forced eviction of as many

as 16,000 Cherokee took place during the fall and winter of 1838–1839 to a new territory in north-eastern Oklahoma (Fibure 1B). During this “Trail of Tears”, an estimated one-fourth of the Cherokee died.

However, at the time of the removal, a few hundred Cherokee successfully escaped to the mountains

of western North Carolina, forming what is now the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians.

In this review, I have consulted the ethnobotanical sources for plants used in Cherokee

traditional medicine [15–24] and I have carried out a literature search using Google Scholar, PubMed,

ResearchGate, and Science Direct for phytochemical analyses on the plant species. Note that in many

instances, the phytochemistry was determined by plants not collected in the south-eastern United

States; many of the species have been introduced to other parts of the world and some species are

native to other continents besides North America. The phytochemistry, therefore, may be affected by

the different geographical and climatic conditions [25]. Sources reporting the phytochemical

constituents, regardless of geographical origin, have been included

Figure 1.(A)

Cherokee territorial lands [26]. (A) ′′Map of the former territorial limits of the Cherokee ′Nation of′ Indians′′, i.e., prior to displacement of Euro-Americans.

Cherokee Aromatic Medicinal Plants and Their Phytochemical Constituents

The plants used by the Cherokee people for traditional medicines for which the phytochemistry

has been investigated are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1.(B)

"Map showing the territory originally assigned Cherokee ′Nation of′ Indians′′, i.e., after the forcible relocation known as the ′′Trail of Tears”

Cherokee Aromatic Medicinal Plants in Use as Herbal Medicine

Achillea millefolium L

Achillea millefolium (yarrow) is native to temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere but

has been introduced worldwide [510]. The traditional medical uses of A. millefolium have been

reviewed and the plant has been used since ancient times as a wound-healing agent and to treat

gastrointestinal complaints [510–512]. Consistent with this, the Cherokee have also used A. millefolium as an antihemorrhagic; for healing wounds, treating bloody hemorrhoids and bloody urine, and for bowel complaints [15,17,510]. In addition, infusions of A. millefolium have been used as a treatment for fever [15,17,510]. Yarrow extract has shown spasmogenic effects on murine and human gastric antrum, consistent with its traditional use to treat dyspepsia [513]. In a double-blind clinical trial, A. millefolium ointment was shown to reduce pain, inflammation, and ecchymosis in episiotomy wound healing [514].

The essential oils of A. millefolium have shown wide variation depending on geographical location

and growing season. Volatile oil samples from Turkey [48] and Macedonia [51] were dominated by

1,8-cineole and camphor, whereas the essential oil from Lavras, Brazil, was rich in chamazulene [49].

The essential oil from Lithuania showed wide variation in composition depending on morphological

type (flower color) as well as plant phenology [50]; γ-terpinene and cadinene (isomer not identified)

were the major components during the flowering phase, but β-pinene was abundant during the

vegetative phase. Conversely, A. millefolium leaf essential oil from Portugal was rich in 1,8-cineole

during the flowering phase, but germacrene D dominated the oil during the vegetative phase [53].

The non-volatile chemical components of A. millefolium are generally dominated by phenolics

(e.g., chlorogenic acid and other quinic acid derivatives) and flavonoids and flavonoid glycosides (e.g.,

luteolin, apigenin, and quercetin, and their glycosides) [38–42,44,46,47]. Chlorogenic acid has shown

in vivo wound-healing properties in rat models [515,516]. Likewise, the flavonoid apigenin [517,518]

as well as an apigenin glycoside [519] have shown in vivo wound-healing effects in rodent models.

Similarly, luteolin [520–522], luteolin-7-O-glucoside [523], quercetin [524–526] and several quercetin

glycosides [527–531] have shown wound-healing effects.

Caulophyllum thalictroides (L.) Michx.

A decoction of the roots of C. thalictroides (blue cohosh) has been used by the Cherokee as an

anticonvulsive (to treat “fits and hysterics”) and antirheumatic [15]. The plant is also used as a

gynecological aid, to promote childbirth and to treat womb inflammation [15].

These traditional uses are in apparent contrast to the observed toxic effects (convulsions, respiratory paralysis) of the plant observed in range animals such as sheep [108]. The rhizome of C. thalictroides contains several quinolizidine alkaloids, including N-methylcytisine (also known as caulophylline), baptifoline, anagyrine, and lupanine [108,110,112]. N-Methylcytisine is known to stimulate the central nervous system, and in high doses causes convulsions followed by paralysis [532]. Acute lupanine toxicity is characterized by neurotoxic effects including decreased cardiac contractility, blocking of ganglionic transmission and contraction of uterine smooth muscle [533].

This latter effect explains the traditional Cherokee use to promote childbirth. Apparently, lupanine, in lower doses, does not exhibit sub-chronic, chronic, reproductive, or mutagenic toxic effects [533].

Both N-methylcytisine [110] and anagyrine [534] have been shown to be teratogenic, however. The aporphine alkaloid magnoflorine, on the other hand, has shown sedative and anxiolytic effects [535] and may be responsible for the anti-convulsive and sedative uses of C. thalictroides in Cherokee traditional medicine.

Lee and co-workers [115] have shown that the oleanolic acid glycosides caulosides A–D exert

anti-inflammatory effects by way of inhibiting expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS)

and the pro-inflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin 6 (IL-6).

The anti-inflammatory effects of C. thalictroides triterpene saponins are consistent with the Cherokee

traditional uses to treat rheumatism and inflammation.

Cimicifuga racemosa (L.) Nutt. (syn. Actaea racemosa L.)

Black cohosh (C. racemosa) has been a popular herbal supplement for many years [536]. The plant

is reputed to possess anti-inflammatory, diuretic, sedative, and antitussive activities [511], and the root

has been reported to have estrogenic activity [537–539]. Fukinolic acid [137] and formononetin [511]

have been reported to be estrogenic constituents of C. racemosa rhizome.

The traditional Cherokee

use of C. racemosa rhizome to stimulate menstruation [15] is consistent with the reported estrogenic

activity. There have been conflicting reports regarding the estrogenic activity of C. racemosa rhizome,

however [540–542], and a survey of 13 populations of C. racemosa in the eastern United States failed

to detect the presence of formononetin [543]. Molecular docking studies have suggested that C.

racemosa triterpenoids are unlikely estrogen receptor binding agents, but any estrogenic activity of C.

racemosa extract is probably due to phenolic components such as cimicifugic acid A, cimicifugic acid B,

cimicifugic acid G, cimiciphenol, cimiciphenone, cimiracemate A, cimiracemate B, cimiracemate C,

cimiracemate D, and fukinolic acid [544]. Although recent evidence suggests the estrogen receptor not

to be a target of C. racemosa phytochemical constituents, other biomolecular targets may be involved.

Rhizome extracts of C. racemosa have been shown to interact with the serotonin receptor [545], the

µ-opioid receptor [546,547] as well as the γ-aminobutryic acid type A (GABAA) receptors [548].

Modulation of these receptors may contribute to some of the biological effects of C. racemosa extracts.

Reviews of several randomized clinical trials have failed to demonstrate efficacy of C. racemosa on

menopausal symptoms [549,550]. However, one randomized, placebo-controlled double-blind clinical

trial with menopausal women, concluded that C. racemosa extract showed superiority over a placebo

in ameliorating menopausal disorders [551]. Clinical studies have generally suggested C. cimicifuga

use to be safe, but there have been some case reports indicating safety concerns [552].

The Cherokee have also used infusions of C. racemosa rhizome to treat rheumatism, coughs,

and colds [15]. Aqueous extracts of C. racemosa have demonstrated reduction of the release

of pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and

interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) in whole blood, and the prominent active component responsible was

isoferulic acid [553]. The ethyl acetate fraction of the aqueous extract of C. racemosa was also shown

to suppress the release of TNF-α, due to cimiracemate A [554]. Aqueous extracts reduced inducible

nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) protein expression as well as iNOS mRNA levels, but did not inhibit

iNOS enzymatic activity; the triterpenoid glycoside 23-epi-26-deoxyactein was found to be the active

principle in the extract [555]. These effects likely explain the anti-inflammatory activities of C. racemosaand their traditional uses to treat rheumatism and other inflammatory diseases.

Hamamelis virginiana L.

Hamamelis virginiana, American witch hazel, is a shrub or small tree, native to eastern North

America. Several Native American tribes have used the plant for numerous medicinal purposes.

Decoctions of the bark or the stems of witch hazel have been used as a topical lotion for cuts, bruises,

insect bites, external inflammations, and other skin problems [15]. In addition, the Cherokee people

took infusions of witch hazel for periodic pains, to treat colds, sore throats, and fevers. Modern

uses of witch hazel include treatment of hemorrhoids, inflammation of the mouth and pharynx

(leaf only), inflammation of the skin, varicose veins, wounds and burns [537]. Hamamelis virginiana

leaves contain up to 10% tannins, including gallic acid, polygalloylglucose, hamamelitannin and

analogs, flavonoids, and proanthocyanidins [511], which are responsible for the observed astringent,

anti-inflammatory, and hemostatic effects [537]. The bark also contains hamamelitannin and analogs,

and proanthocyanidins [511].

The aqueous ethanol extract of H. virginiana showed anti-inflammatory activity in the croton

oil mouse ear edema test [556] as well as the induced rat paw edema assay, confirming its use

as an anti-inflammatory agent [557]. The extract also showed notable antiviral activity against

Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) [556]. Hamamelitannin and galloylated proanthocyanidins

from H. virginiana were found to be potent inhibitors of 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX) [558]. Hamamelis

proanthocyanidins were found to stimulate cell growth of keratinocytes, enhancing cell growth, and

are likely responsible for the dermatological use of tannin-containing witch hazel preparations [559].

Hamamelis tannins have also shown cytotoxic activity against HT-29 human colorectal adenocarcinoma cells [223] and antiviral activity against influenza A virus and human papillomavirus [560].

The anti-inflammatory activity of witch hazel was demonstrated in a clinical study using a lotion

prepared from H. virginiana distillate, which showed suppression of erythema after ultraviolet (UVB)

light exposure [561]. Similarly, in a clinical trial with patients suffering from atopic eczema, a cream

containing H. virginiana distillate significantly reduced skin desquamation, itching and redness [562].

Of course, H. virginiana distillate will not contain tannins.

Hydrastis canadensis L.

Goldenseal (Hydrastis canadensis), a perennial herb in the Ranunculaceae, is native to eastern

North America from Ontario, Canada, south to Alabama and Georgia [563]. The Cherokee used the

root decoction of goldenseal as a tonic and wash for local inflammations; took the root decoction orally

to treat cancer, dyspepsia, and general debility [15]. Goldenseal is still used in herbal medicine to

control muscle spasms, treat cancer, increase blood pressure, treat gastrointestinal disorders, manage

painful and heavy menstruation, treat infections topically, and reduce swelling [537,564].

The major components in goldenseal root are isoquinoline alkaloids hydrastine, berberine, and

canadine, and berberine likely accounts for the biological activities of goldenseal. Berberine has

shown in vitro cytotoxic activity to HeLa human epitheloid cervix carcinoma, SK-OV-3 human

ovarian carcinoma, HEp2 human laryngeal carcinoma, HT-29 human colorectal adenocarcinoma,

MKN-45 human gastric cancer, HepG2 human hepatocellular carcinoma, MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231

human breast adenocarcinoma cell lines [565–568]. The cytotoxicity of berberine can be attributed

to DNA intercalation [569–571] and modulation of the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

(HER2)/phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (Akt) signaling pathway [572,573].

Berberine has also shown antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus [238,574], and Helicobacter pylori [453]; antiparasitic activity against Entamoeba histolytica, Giardia lamblia, Trichomonas vaginalis, Trypanosoma brucei, Trypanosoma congolense, Leishmania braziliensis panamensis, Leishmania major, and Plasmodium falciparum [575–578]; and anti-inflammatory activity in a serotonin-induced mouse paw edema assay [579]. In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial with patients suffering from acute watery diarrhea due to cholera, berberine showed a significant reduction in stool volume compared to the placebo [580]. Several clinical studies have demonstrated antihyperlipidemic effects of berberine in humans [581]

Juncus effusus L

Juncus effusus (common rush) is native to North and South America, Europe, Asia, and

Africa [563]. There are numerous varieties and subspecies of J. effusus with at least two in eastern

North America [582]. The Cherokee took a decoction of the plant as an emetic, while an infusion was

used to wash babies to strengthen them and prevent lameness [15]. In Chinese Traditional Medicine

(TCM), J. effusus is used as a sedative, anxiolytic, antipyretic, and to reduce swelling. Extracts of

J. effusus have revealed several cinnamoylglycerides [252,253], cycloartane triterpenoids [255–257],

phenanthrenes [258–264,266,267,269–272,583,584], and pyrenes [265,268]. Dehydroeffusol, effusol,

and juncusol, phenanthrenes isolated from J. effusus, have shown anxiolytic and sedative effects in a

mouse model [264,271], likely due to modulation of the gamma-amino butyric acid type A (GABAA)

receptor [272]. The GABAA modulatory activity may account for the TCM use of J. effusus as a sedative

and anxiolytic agent. Several J. effusus phenanthrenes have shown inhibition of NO production in

lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-activated murine macrophage RAW 264.7 cells, indicating anti-inflammatory

activity [270].

Panax quinquefolius L

American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius) is a member of the Araliaceae and is native to eastern

North America [585]. Ginseng root from P. ginseng or P. notoginseng, has been used for thousands

of years in the Asian traditional medicine. Panax quinquefolius is currently cultivated in the United

States, Canada, and China, and is used as a medical tonic worldwide. Native Americans have used P.

quinquefolius for numerous medical problems as well as a general tonic [15], and European settlers had

also utilized this plant for similar purposes [586]. The Cherokee used the root as an expectorant, to

treat colic, oral thrush, and as a general tonic [15].

The phytochemistry and pharmacology of P. quinquefolius has been reviewed several

times [333,339,341,342]. The major components in P. quinquefolius roots are triterpenoid glycosides,

the ginsenosides, as well as several polyacetylenes. The ginsenosides have shown anti-inflammatory,

antiproliferative, hepatoprotective, cardioprotective, neuroprotective, cholesterol-lowering, and

cognitive improvement [340].

Several clinical trials have been carried out using P. quinquefolius extracts. In terms of cognitive

function, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controled crossover trial, P. quinquefolius extract showed significant improvement in working memory, choice reaction time and “calmness” [587]. A clinical trial to study the effects of P. quinquefolius extract on cancer-related fatigue showed a promising significant trend in relieving fatigue [588]. Panax quinquefolius extracts were found to be clinically effective in preventing upper respiratory infections in healthy adult senior citizens [589,590].

Sanguinaria canadensis L.

Bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis, Papaveraceae) is native to eastern North America [591]. The

plant has been used by Native Americans as a traditional medicine for a variety of ailments [455].

The Cherokee used a decoction of the root, in small doses, for coughs, lung inflammations, and

croup, and a root infusion was used as a wash for ulcers and sores [15]. The roots are rich in

isoquinoline alkaloids, including sanguinarine, chelerythrine, sanguilutine, chelilutine, sanguirubine,

chelirubine, protopine, and allocryptopine [455]. The traditional Cherokee uses of bloodroot as a cough

medicine/respiratory aid as well as for treating ulcers and sores can be attributed to the antimicrobial

activities of the isoquinoline alkaloids [592]. Thus, for example, sanguinarine has shown antimicrobial

activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) [593], biofilm-forming Candida

spp. [594], Mycobacterium spp. [452], and Helicobacter pylori [453].

Scutellaria lateriflora L

Infusions of the roots of blue skullcap (Scutellaria lateriflora, Lamiaceae) were used by the Cherokee

for monthly periods and to treat diarrhea; root decoctions were used as an emetic to expel afterbirth

and to remedy breast pains [15]. Interestingly, the aerial parts, rather than the roots, are currently used

as an herbal medicine as an anxiolytic, sedative and antispasmodic [511,537,595,596].

The phytochemistry and pharmacology of S. lateriflora have been reviewed [469].

The secondary metabolites from the aerial parts of S. lateriflora are dominated by flavonoid glycosides (baicalin, dihydrobaicalin, lateriflorin, ikonnikoside I, scutellarin (scutellarein-7-O-glucuronide), and oroxylin A-7-O-glucuronide, and 2-methoxy-chrysin-7-O-glucuronide), flavonoid aglycones (baicalein, oroxylin A, wogonin, and lateriflorein), phenylpropanoids (caffeic acid, cinnamic acid, p-coumaric acid, and ferulic acid), and clerodane diterpenoids (scutelaterin A, scutelaterin B, scutelaterin C, ajugapitin,

and scutecyprol A) [469]. The essential oil from the aerial parts of S. lateriflora (collected in northern

Iran) was composed largely of sesquiterpene hydrocarbons, δ-cadinene (27%), calamenene (15.2%),

β-elemene (9.2%), α-cubenene (4.2%), α-humulene (4.2%), and α-bergamotene (2.8%) [470].

The flavonoids scutellarin and baicalin and the phenylpropanoid ferulic acid have shown in vitro

estrogenic effects [597,598], and may be responsible for the traditional Cherokee uses of S. lateriflora.

Consistent with the current herbal medicinal use of S. lateriflora, the plant has shown

anti-convulsant activity in rodent models of acute seizures, attributable to the flavonoid

constituents [474]. Baicalin has shown anti-convulsant activity in pilocarpine-induced epileptic

model in rats [599], and wogonin has shown anti-convulsant effects on chemically-induced and

electroshock-induced seizures in rodents [600]. In addition, scutellarin has shown relaxant activity

using rodent aorta models [601,602], while wogonin showed smooth muscle relaxant activity in rat

aorta [603] and rat uterine smooth muscle [604]. On the other hand, both baicalin and baicalein

inhibited NO-mediated relaxation of rat aortic rings [605]. Baicalein and baicalin have shown

anxiolytic activity [606]. Apparently, baicalin and wogonin exert their anxiolytic effects through

allosteric modulation of the GABAA receptor by way of interaction at the benzodiazepine site [607,608].

Conversely, baicalein promotes anxiolytic effects via interaction with non-benzodiazepine sites of the

GABAA receptor [609]. There have apparently been no clinical trials on the root extracts of S. lateriflora.

However, in randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover clinical trials, the anxiolytic

effects of S. lateriflora herbal treatments significantly enhanced overall mood without reducing cognition

or energy [610,611]

Cherokee Aromatic Medicinal Plants and Their Phytochemical Constituents

Conclusions

This is not a complete list of the phytochemistry of Cherokee aromatic medicinal plants. Numerous

plants described in the Cherokee ethnobotanical literature [15–24] have not been investigated

for phytochemical constituents or pharmacological activity. In addition, in many instances the

phytochemistry is not sufficiently characterized, particularly in terms of the plant tissues used in

Cherokee traditional medicine. In this review, there are numerous instances where the phytochemical

constituents and the biological activities associated with them correlate with the traditional Cherokee

uses of the plant, but there are several instances where there is no apparent correlation. Therefore,

much work is needed to add to our knowledge of the pharmacological properties of the chemical

components, not to mention potential synergistic or antagonistic interactions.

Funding: This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments: This work was carried out as part of the activities of the Aromatic Plant Research Center (APRC, https://aromaticplant.org/).

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

1. Yuan, H.; Ma, Q.; Ye, L.; Piao, G. The traditional medicine and modern medicine from natural products. Molecules 2016, 21, 559. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

2. Qin, G.; Xu, R. Recent advances on bioactive natural products from Chinese medicinal plants. Med. Res. Rev. 1998, 18, 375–382. [CrossRef]

3. Patwardhan, B.; Vaidya, A.D.B.; Chorghade, M. Ayurveda and natural products drug discovery. Curr. Sci. 2004, 86, 789–799.

4. Duke, J.A.; Bogenschutz-Godwin, M.J.; Ottesen, A.R. Duke’s Handbook of Medicinal Plants of Latin America; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2009.

5. Atanasov, A.G.; Waltenberger, B.; Pferschy-Wenzig, E.M.; Linder, T.; Wawrosch, C.; Uhrin, P.; Temml, V.; Wang, L.; Schwaiger, S.; Heiss, E.H.; et al. Discovery and resupply of pharmacologically active plant-derived natural products: A review. Biotechnol. Adv. 2015, 33, 1582–1614. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

6. DeCorte, B.L. Underexplored opportunities for natural products in drug discovery. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 9295–9304. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

7. Newman, D.J.; Cragg, G.M. Natural products as sources of new drugs from 1981 to 2014. J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79, 629–661. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

8. Pinheiro, L.C.S.; Feitosa, L.M.; da Silveira, F.F.; Boechat, N. Current antimalarial therapies and advances

in the development of semi-synthetic artemisinin derivatives. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2018, 90, 1251–1271. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

9. Bunkar, A.R. Therapeutic uses of Rauwolfia serpentina. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Res. 2017, 2, 23–26.

10. Monzote Fidalgo, L. Essential oil from Chenopodium ambrosioides as a promising antileishmanial agent. Nat.

Prod. Commun. 2007, 2, 1257–1262.

11. Cave, A.A. The Pequot War; University of Massachusetts Press: Amherst, MA, USA, 1996.

12. Roundtree, H.C. Pocahantas’s People: The Powhatan Indians of Virginia through Four Centuries; University of Oklahoma Press: Norman, OK, USA, 1990.

13. Ehle, J. Trail of Tears: The Rise and Fall of the Cherokee Nation; Anchor Books: New York, NY, USA, 1988.

14. Brown, D. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West; Picador: New York, NY, USA, 2007.

15. Moerman, D.E. Native American Ethnobotany; Timber Press, Inc.: Portland, OR, USA, 1998.

16. Hutchens, A.R. Indian Herbalogy of North America; Shambala Publications: Boulder, CO, USA, 1991.

17. Hamel, P.B.; Chiltoskey, M.U. Cherokee Plants and Their Uses—A 400 Year History; Herald Publishing Company: Sylva, NC, USA, 1975.

18. Garrett, J.T. The Cherokee Herbal; Bear & Company: Rochester, VT, USA, 2003.

19. Mooney, J. The sacred formulas of the Cherokees. In Seventh Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology; Powell, J.W., Ed.; Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1891; pp. 301–397.

20. Banks, W.H. Ethnobotany of the Cherokee Indians. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, USA, 1953.

21. Cozzo, D.N. Ethnobotanical Classifiction System and Medical Ethnobotany of the Eastern Band of the Cherokee Indians. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA, 2004.

22. Winston, D. Nvwoti; Cherokee medicine and ethnobotany. J. Am. Herb. Guild 2001, 2, 45–49.

23. Core, E.L. Ethnobotany of the southern Appalachian Aborigines. Econ. Bot. 1967, 21, 199–214. [CrossRef]

24. Ray, L.E. Podophyllum peltatum and observations on the Creek and Cherokee Indians: William Bartram’s preservation of Native American pharmacology. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2009, 82, 25–36. [PubMed]

25. Vanhaelen, M.; Lejoly, J.; Hanocq, M.; Molle, L. Climatic and geographical aspects of medicinal plant

constituents. In The Medicinal Plant Industry; Wijesekera, R.O.B., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1991; pp. 59–76.

26. Royce, C.C. Map of the Former Territorial Limits of the Cherokee Nation of “Indians”; Map Showing the Territory Originally Assigned Cherokee “Nation of” Indians. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/99446145/ (accessed on 24 October 2018).

27. Abou-Zaid, M.M.; Nozzolillo, C. 1-O-galloyl-α-L-rhamnose from Acer rubrum. Phytochemistry 1999, 52, 1629–1631. [CrossRef]

28. Abou-Zaid, M.M.; Helson, B.V.; Nozzolillo, C.; Arnason, J.T. Ethyl m-digallate from red maple, Acer rubrum L., as the major resistance factor to forest tent caterpillar, Malacosoma disstria Hbn. J. Chem. Ecol. 2001, 27, 2517–2527. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

29. Ma, H. Phytochemical and Biological Investigation of Gallotannins from Red Maple (Acer rubrum) Species. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Rhode Island, Kingston, RI, USA, 2014.

30. Wan, C.; Yuan, T.; Xie, M.; Seeram, N.P. Acer rubrum phenolics include A-type procyanidins and a chalcone. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2012, 44, 1–3. [CrossRef]

31. Wan, C.; Yuan, T.; Li, L.; Kandhi, V.; Cech, N.B.; Xie, M.; Seeram, N.P. Maplexins, new α-glucosidase inhibitors from red maple (Acer rubrum) stems. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 597–600. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

32. Yuan, T.; Wan, C.; Liu, K.; Seeram, N.P. New maplexins F-I and phenolic glycosides from red maple (Acer rubrum) bark. Tetrahedron 2012, 68, 959–964. [CrossRef]

33. González-Sarrías, A.; Yuan, T.; Seeram, N.P. Cytotoxicity and structure activity relationship studies of maplexins A–I, gallotannins from red maple (Acer rubrum). Food Chem. Toxicol. 2012, 50, 1369–1376.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

34. Zhang, Y.; Ma, H.; Yuan, T.; Seeram, N.P. Red maple (Acer rubrum) aerial parts as a source of bioactive phenolics. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2015, 10, 1409–1412. [PubMed]

35. Bailey, A.E.; Asplund, R.O.; Ali, M.S. Isolation of methyl gallate as the antitumor principle of Acer saccharinum. J. Nat. Prod. 1986, 49, 1149–1150. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

36. Bin Muhsinah, A.; Ma, H.; DaSilva, N.A.; Yuan, T.; Seeram, N.P. Bioactive glucitol-core containing

gallotannins and other phytochemicals from silver maple (Acer saccharinum) leaves. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2017, 12, 83–84.

37. Falk, A.J.; Smolenski, S.J.; Bauer, L.; Bell, C.L. Isolation and identification of three new flavones from Achillea millefolium L. J. Pharm. Sci. 1975, 64, 1838–1842. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

38. Benetis, R.; Radušiene, J.; Janulis, V. Variability of phenolic compounds in flowers of ˙ Achillea millefolium wild populations in Lithuania. Medicina 2008, 44, 775–781. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

39. Glasl, S.; Mucaji, P.; Werner, I.; Presser, A.; Jurenitsch, J. Sesquiterpenes and flavonoid aglycones from a Hungarian taxon of the Achillea millefolium group. Z. Naturforsch. 2002, 57, 976–982. [CrossRef]

40. Vitalini, S.; Beretta, G.; Iriti, M.; Orsenigo, S.; Basilico, N.; Dall’Acqua, S.; Iorizzi, M.; Fico, G. Phenolic

compounds from Achillea millefolium L. and their bioactivity. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2011, 58, 203–209. [PubMed]

41. Dias, M.I.; Barros, L.; Dueñas, M.; Pereira, E.; Carvalho, A.M.; Alves, R.C.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P.;

Santos-Buelga, C.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Chemical composition of wild and commercial Achillea millefolium

L. and bioactivity of the methanolic extract, infusion and decoction. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 4152–4160.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

42. Dall’Acqua, S.; Bolego, C.; Cignarella, A.; Gaion, R.M.; Innocenti, G. Vasoprotective activity of standardized

Achillea millefolium extract. Phytomedicine 2011, 18, 1031–1036. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

43. Tozyo, T.; Yoshimura, Y.; Sakurai, K.; Uchida, N.; Takeda, Y.; Nakai, H.; Ishi, H. Novel antitumor

sesquiterpenoids in Achillea millefolium. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1994, 42, 1096–1100. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

44. Innocenti, G.; Vegeto, E.; Dall’Acqua, S.; Ciana, P.; Giorgetti, M.; Agradi, E.; Sozzi, A.; Fico, G.; Tomè, F.

In vitro estrogenic activity of Achillea millefolium L. Phytomedicine 2007, 14, 147–152. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

45. Pires, J.M.; Mendes, F.R.; Negri, G.; Duarte-Almeida, J.M.; Carlini, E.A. Antinociceptive peripheral effect of

Achillea millefolium L. and Artemisia vulgaris L.: Both plants known popularly by brand names of analgesic drugs. Phyther. Res. 2009, 23, 212–219. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

46. Guédon, D.; Abbe, P.; Lamaison, J.L. Leaf and flower head flavonoids of Achillea millefolium L. subspecies.

Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 1993, 21, 607–611. [CrossRef]

47. Csupor-Löffler, B.; Hajdú, Z.; Zupkó, I.; Réthy, B.; Falkay, G.; Forgo, P.; Hohmann, J. Antiproliferative

effect of flavonoids and sesquiterpenoids from Achillea millefolium s.l. on cultured human tumour cell lines. Phyther. Res. 2009, 23, 672–676. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

48. Candan, F.; Unlu, M.; Tepe, B.; Daferera, D.; Polissiou, M.; Sökmen, A.; Akpulat, H.A. Antioxidant and

antimicrobial activity of the essential oil and methanol extracts of Achillea millefolium subsp. millefolium Afan. (Asteraceae). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2003, 87, 215–220. [CrossRef]

49. Santoro, G.F.; Cardoso, M.G.; Gustavo, L.; Guimarães, L.G.L.; Mendonça, L.Z.; Soares, M.J. Trypanosoma cruzi:

Activity of essential oils from Achillea millefolium L., Syzygium aromaticum L. and Ocimum basilicum L. on epimastigotes and trypomastigotes. Exp. Parasitol. 2007, 116, 283–290. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

50. Bimbiraite, K.; Ragižinskien ˙ e, O.; Maruška, A.; Kornyšova, O. Comparison of the chemical composition of ˙ four yarrow (Achillea millefolium L.) morphotypes. Biologija 2008, 54, 208–212. [CrossRef]

51. Bocevska, M.; Sovová, H. Supercritical CO2 extraction of essential oil from yarrow. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2007, 40, 360–367. [CrossRef]

52. Barghamadi, A.; Mehrdad, M.; Sefidkon, F.; Yamini, Y.; Khajeh, M. Comparison of the volatiles of Achillea millefolium L. obtained by supercritical carbon dioxide extraction and hydrodistillation Methods. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2009, 21, 259–264. [CrossRef]

53. Figueiredo, A.C.; Barroso, J.G.; Pais, M.S.S.; Scheffer, J.J.C. Composition of the essential oils from leaves and flowers of Achillea millefolium L. ssp. millefolium. Flavour Fragr. J. 1992, 7, 219–222. [CrossRef]

54. Zhang, Z.; Li, S.; Zhang, S.; Gorenstein, D. Triterpenoid saponins from the fruits of Aesculus pavia.

Phytochemistry 2006, 67, 784–794. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

55. Zhang, Z.; Li, S. Cytotoxic triterpenoid saponins from the fruits of Aesculus pavia L. Phytochemistry 2007, 68, 2075–2086. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

56. Sun, Z.; Zhang, M.; Wu, Y.; Wan, A.; Zhang, R. Bioactive saponins from the fruits of Aesculus pavia L.

Fitoterapia 2011, 82, 1106–1109. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

57. Curir, P.; Galeotti, F.; Dolci, M.; Barile, E.; Lanzotti, V. Pavietin, a coumarin from Aesculus pavia with antifungal activity. J. Nat. Prod. 2007, 70, 1668–1671. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

58. Ferracini, C.; Curir, P.; Dolci, M.; Lanzotti, V.; Alma, A. Aesculus pavia foliar saponins: Defensive role against the leafminer Cameraria ohridella. Pest Manag. Sci. 2010, 66, 767–772. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

59. Lanzotti, V.; Termolino, P.; Dolci, M.; Curir, P. Paviosides A–H, eight new oleane type saponins from Aesculus pavia with cytotoxic activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2012, 20, 3280–3286. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

60. Beier, R.C.; Norman, J.O.; Reagor, J.C.; Rees, M.S.; Mundy, B.P. Isolation of the major component in white snakeroot that is toxic after microsomal activation: Possible explanation of sporadic toxicity of white snakeroot plants and extracts. Nat. Toxins 1993, 1, 286–293. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

61. Lee, S.T.; Davis, T.Z.; Gerdner, D.R.; Stegelmeier, B.L.; Evans, T.J. Quantitative method for the measurement of three benzofuran ketones in rayless goldenrod (Isocoma pluriflora) and white snakeroot (Ageratina altissima) by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 5639–5643. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

62. Lee, S.T.; Davis, T.Z.; Gardner, D.R.; Colegate, S.M.; Cook, D.; Green, B.T.; Meyerholtz, K.A.; Wilson, C.R.; Stegelmeier, B.L.; Evans, T.J. Tremetone and structurally related compounds in white snakeroot (Ageratina altissima): A plant associated with trembles and milk sickness. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 8560–8565. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

63. Fritsch, R.M.; Keusgen, M. Occurrence and taxonomic significance of cysteine sulphoxides in the genus Allium L. (Alliaceae). Phytochemistry 2006, 67, 1127–1135. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

64. Sobolewska, D.; Michalska, K.; Podolak, I.; Grabowska, K. Steroidal saponins from the genus Allium.

Phytochem. Rev. 2016, 15, 1–35. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

65. Calvey, E.M.; White, K.D.; Matusik, J.E.; Sha, D.; Block, E. Allium chemistry: Identification of organosulfur compounds in ramp (Allium tricoccum) homogenates. Phytochemistry 1998, 49, 359–364. [CrossRef]

66. Chen, S.; Snyder, J.K. Molluscicidal saponins from Allium vineale. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987, 28, 5603–5606. [CrossRef]

67. Chen, S.; Snyder, J.K. Diosgenin-bearing mulluscicidal saponins from Allium vineale: An NMR approach for the structural assignment of oligosaccharide units. J. Org. Chem. 1989, 54, 3679–3689. [CrossRef]

68. Demirtas, I.; Erenler, R.; Elmastas, M.; Goktasoglu, A. Studies on the antioxidant potential of flavones of Allium vineale isolated from its water-soluble fraction. Food Chem. 2013, 136, 34–40. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

69. Satyal, P.; Craft, J.D.; Dosoky, N.S.; Setzer, W.N. The chemical compositions of the volatile oils of garlic (Allium sativum) and wild garlic (Allium vineale). Foods 2017, 6, 63. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

70. Li, H.; O’Neill, T.; Webster, D.; Johnson, J.A.; Gray, C.A. Anti-mycobacterial diynes from the Canadian medicinal plant Aralia nudicaulis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 140, 141–144. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

71. Davé, P.C.; Vogler, B.; Setzer, W.N. Chemical compositions of the leaf essential oils of Aralia spinosa from three habitats in Northern Alabama. Am. J. Plant Sci. 2011, 02, 507–510. [CrossRef]

72. Wolf, S.J.; Denford, K.E. Flavonoid variation in Arnica cordifolia: An apomictic polyploid complex. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 1983, 11, 111–114. [CrossRef]

73. Merfort, I.; Wendisch, D. Sesquiterpene lactones of Arnica cordifolia, subgenus austromontana. Phytochemistry 1993, 34, 1436–1437. [CrossRef]

74. Nematollahi, F.; Rustaiyan, A.; Larijani, K.; Madimi, M.; Masoudi, S. Essential oil composition of Artemisia biennis Willd. and Pulicaria undulata (L.) C.A. Mey., two Compositae herbs growing wild in Iran. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2006, 18, 339–341. [CrossRef]

75. Lopes-Lutz, D.; Alviano, D.S.; Alviano, C.S.; Kolodziejczyk, P.P. Screening of chemical composition,

antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of Artemisia essential oils. Phytochemistry 2008, 69, 1732–1738. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

76. Jeong, S.Y.; Jun, D.Y.; Kim, Y.H.; Min, B.-S.; Min, B.K.; Woo, M.H. Monoterpenoids from the aerial parts of Aruncus dioicus var. kamtschaticus and their antioxidant and cytotoxic activities. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 3252–3256. [PubMed]

77. Han, C.R.; Jun, D.Y.; Woo, H.J.; Jeong, S.-Y.; Woo, M.-H.; Kim, Y.H. Induction of microtubule-damage, mitotic arrest, Bcl-2 phosphorylation, Bak activation, and mitochondria-dependent caspase cascade is involved in human Jurkat T-cell apoptosis by aruncin B from Aruncus dioicus var. kamtschaticus. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 945–953. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

78. Zhao, B.T.; Jeong, S.Y.; Vu, V.D.; Min, B.S.; Kim, Y.H.; Woo, M.H. Cytotoxic and anti-oxidant constituents from the aerial parts of Aruncus dioicus var. kamtschaticus. Nat. Prod. Sci. 2013, 19, 6670.

79. Vo, Q.H.; Nguyen, P.H.; Zhao, B.T.; Thi, Y.N.; Nguyen, D.H.; Kim, W.I.; Seo, U.M.; Min, B.S.; Woo, M.H.

Bioactive constituents from the n-butanolic fraction of Aruncus dioicus var. kamtschaticus. Nat. Prod. Sci. 2014,20, 274–280

80. Fusani, P.; Piwowarski, J.P.; Zidorn, C.; Kiss, A.K.; Scartezzini, F.; Granica, S. Seasonal variation in secondary metabolites of edible shoots of Buck’s beard [Aruncus dioicus (Walter) Fernald (Rosaceae)]. Food Chem. 2016, 202, 23–30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

81. Iwashina, T.; Kitajima, J. Chalcone and flavonol glycosides from Asarum canadense (Aristolochiaceae). Phytochemistry 2000, 55, 971–974. [CrossRef]

82. Bauer, L.; Bell, C.L.; Gearien, J.E.; Takeda, H. Constituents of the rhizome of Asarum canadense. J. Pharm. Sci. 1967, 56, 336–343. [CrossRef]

83. Motto, M.G.; Secord, N.J. Composition of the essential oil from Asarum canadense. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1985, 33, 789–791. [CrossRef]

84. Bélanger, A.; Collin, G.; Garneau, F.-X.; Gagnon, H.; Pichette, A. Aromas from Quebec. II. Composition of the essential oil of the rhizomes and roots of Asarum canadense L. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2010, 22, 164–169. [CrossRef]

85. Garneau, F.; Collin, G.; Gagnon, H. Chemical composition and stability of the hydrosols obtained during essential oil production. I. The case of Melissa officinalis L. and Asarum canadense L. Am. J. Essent. Oils Nat. Prod. 2014, 2, 54–62.

86. Abe, F.; Yamauchi, T. An androstane bioside and 3’-thiazolidinone derivatives of doubly-linked cardenolide glycosides from the roots of Asclepias tuberosa. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2000, 48, 991–993. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

87. Abe, F.; Yamauchi, T. Pregnane glycosides from the roots of Asclepias tuberosa. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2000, 48, 1017–1022. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

88. Warashina, T.; Noro, T. 8,14-Secopregnane glycosides from the aerial parts of Asclepias tuberosa. Phytochemistry 2009, 70, 1294–1304. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

89. Warashina, T.; Noro, T. 8,12;8,20-Diepoxy-8,14-secopregnane glycosides from the aerial parts of Asclepias tuberosa. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2010, 58, 172–179. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

90. Warashina, T.; Umehara, K.; Miyase, T.; Noro, T. 8,12;8,20-Diepoxy-8,14-secopregnane glycosides from roots of Asclepias tuberosa and their effect on proliferation of human skin fibroblasts. Phytochemistry 2011, 72, 1865–1875. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

91. Lebreton, P.; Markham, K.R.; Swift, W.T., III; Mabry, T.J. Flavonoids of Baptista australis (Leguminosae). Phytochemistry 1967, 6, 1675–1680. [CrossRef]

92. Markham, K.R.; Swift, W.T.; Mabry, T.J. A new isoflavone glycoside from Baptisia australis. J. Org. Chem. 1968, 33, 462–464. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

93. Fraser, A.M.; Robins, D.J. Incorporation of enantiomeric [1 2H]cadaverines into the quinolizindine alkaloids (+)-sparteine and (-)-N-methylcytisine in Baptisia australis. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1986, 1986, 545–547. [CrossRef]

94. Zenk, M.H.; Rueffer, M.; Amann, M.; Deus-Neumann, B. Benzylisoquinoline biosynthesis by cultivated plant cells and isolated enzymes. J. Nat. Prod. 1985, 48, 725–738. [CrossRef]

95. Woods, K.E.; Jones, C.D.; Setzer, W.N. Bioactivities and compositions of Betula nigra essential oils. J. Med. Act. Plants 2013, 2, 1–9.

96. Hua, Y.; Bentley, M.D.; Cole, B.J.W.; Murray, K.D.; Alford, A.R. Triterpenes from the outer bark of Betula nigra. J. Wood Chem. Technol. 1991, 11, 503–516. [CrossRef]

97. Wollenweber, E. Rare methoxy flavonoids from buds of Betula nigra. Phytochemistry 1976, 15, 438–439.[CrossRef]

98. Wollenweber, E. New flavonoids from Betula nigra. Phytochemistry 1977, 16, 295. [CrossRef]

99. Tellez, M.R.; Dayan, F.E.; Schrader, K.K.; Wedge, D.E.; Duke, S.O. Composition and some biological activitiesof the essential oil of Callicarpa americana (L.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 3008–3012. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

100. Cantrell, C.L.; Klun, J.A.; Bryson, C.T.; Kobaisy, M.; Duke, S.O. Isolation and identification of mosquito bite deterrent terpenoids from leaves of American (Callicarpa americana) and Japanese (Callicarpa japonica) beautyberry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 5948–5953. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

101. Carroll, J.F.; Cantrell, C.L.; Klun, J.A.; Kramer, M. Repellency of two terpenoid compounds isolated from Callicarpa americana (Lamiaceae) against Ixodes scapularis and Amblyomma americanum ticks. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2007, 41, 215–224. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

102. Jones, W.P.; Lobo-Echeverri, T.; Mi, Q.; Chai, H.-B.; Soejarto, D.D.; Cordell, G.A.; Swanson, S.M.;

Kinghorn, A.D. Cytotoxic constituents from the fruiting branches of Callicarpa americana collected in southern Florida. J. Nat. Prod. 2007, 70, 372–377. [CrossRef] [Pub

103. Collins, R.P.; Chang, N.; Knaak, L.E. Anthocyanins in Calycanthus floridus. Am. Midl. Nat. 1969, 82, 633–637.

[CrossRef]

104. Miller, E.R.; Taylor, G.W.; Eskew, M.H. The volatile oil of Calycanthus floridus. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1914, 36,

2182–2187. [CrossRef]

105. Collins, R.P.; Halim, A.F. Essential leaf oils in Calycanthus floridus. Planta Med. 1971, 20, 241–243. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

106. Akhlaghi, H. Chemical composition of the essential oil from flowers of Calycanthus floridus L. var. oblongifolius

(Nutt.) D.E. Boufford & S.A. Spongberg from Iran. J. Pharm. Heal. Sci. 2014, 2, 111–114.

107. Akhlaghi, H. Chemical composition of the essential oil from stems of Calycanthus floridus L. var. oblongifolius

from Iran. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2008, 44, 661–662. [CrossRef]

108. Woldemariam, T.Z.; Betz, J.M.; Houghton, P.J. Analysis of aporphine and quinolizidine alkaloids from

Caulophyllum thalictroides by densitometry and HPLC. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 1997, 15, 839–843. [CrossRef]

109. Betz, J.M.; Andrzejewski, D.; Troy, A.; Casey, R.E.; Obermeyer, W.R.; Page, S.W.; Woldemariam, T.Z. Gas

chromatographic determination of toxic quinolizidine alkaloids in blue cohosh Caulophyllum thalictroides (L.)

Michx. Phytochem. Anal. 1998, 9, 232–236. [CrossRef]

110. Kennelly, E.J.; Flynn, T.J.; Mazzola, E.P.; Roach, J.A.; McCloud, T.G.; Danford, D.E.; Betz, J.M. Detecting

potential teratogenic alkaloids from blue cohosh rhizomes using an in vitro rat embryo culture. J. Nat. Prod.

1999, 62, 1385–1389. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

111. Ali, Z.; Khan, I.A. Alkaloids and saponins from blue cohosh. Phytochemistry 2008, 69, 1037–1042. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

112. Madgula, V.L.M.; Ali, Z.; Smillie, T.; Khan, I.; Walker, L.A.; Khan, S.I. Alkaloids and saponins as cytochrome

P450 inhibitors from blue cohosh (Caulophyllum thalictroides) in an in vitro assay. Planta Med. 2009, 75,

329–332. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

113. Jhoo, J.-W.; Sang, S.; He, K.; Cheng, X.; Zhu, N.; Stark, R.E.; Zheng, Q.Y.; Rosen, R.T.; Ho, C.-T.

Characterization of the triterpene saponins of the roots and rhizomes of blue cohosh (Caulophyllum

thalictroides). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 5969–5974. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

114. Matsuo, Y.; Watanabe, K.; Mimaki, Y. Triterpene glycosides from the underground parts of Caulophyllum

thalictroides. J. Nat. Prod. 2009, 72, 1155–1160. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

115. Lee, Y.; Jung, J.-C.; Ali, Z.; Khan, I.A.; Oh, S. Anti-inflammatory effect of triterpene saponins isolated from

blue cohosh (Caulophyllum thalictroides). Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 2012, 798192. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

116. Warnhoff, E.W.; Pradhan, S.K.; Ma, J.C. Ceanothus alkaloids I. Isolation, separation, and characterization. Can.

J. Chem. 1965, 53, 2594–2602. [CrossRef]

117. Klein, F.K.; Rapoport, H. Ceanothus alkaloids. Americine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1968, 90, 2398–2404. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

118. Servis, R.E.; Kosak, A.I.; Tschesche, R.; Frohberg, E.; Fehlhaber, H.-W. Peptide alkaloids from Ceanothus

americanus L. (Rhamnaceae). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1969, 91, 5619–5624. [CrossRef]

119. Steinberg, K.M.; Satyal, P.; Setzer, W.N. Chemical composition of the bark essential oil of Cercis canadensis L.

(Fabaceae). Am. J. Essent. Oils Nat. Prod. 2017, 5, 15–17.

120. Bowers, M.D.; Boockvar, K.; Collinge, S.K. Iridoid glycosides of Chelone glabra (Scrophulariaceae) and their

sequestration by larvae of a wawfly, Tenthredo grandis (Tenthredinidae). J. Chem. Ecol. 1993, 19, 815–823.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

121. St. Pyrek, J. Sesquiterpene lactones of Cinchorium intybus and Leontodon autumnalis. Phytochemistry 1985, 24,

186–188. [CrossRef]

122. Kisiel, W.; Zieli´nska, K. Guaianolides from Cichorium intybus and structure revision of Cichorium

sesquiterpene lactones. Phytochemistry 2001, 57, 523–527. [CrossRef]

123. Bischoff, T.A.; Kelley, C.J.; Karchesy, Y.; Laurantos, M.; Nguyen-Dinh, P.; Arefi, A.G. Antimalarial activity of

lactucin lnd lactucopicrin: Sesquiterpene lactones isolated from Cichorium intybus L. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004,

95, 455–457. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

124. Wesołowska, A.; Nikiforuk, A.; Michalska, K.; Kisiel, W.; Chojnacka-Wójcik, E. Analgesic and sedative

activities of lactucin and some lactucin-like guaianolides in mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2006, 107, 254–258.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

125. Nørbæk, R.; Nielsen, K.; Kondo, T. Anthocyanins from flowers of Cichorium intybus. Phytochemistry 2002, 60,

357–359. [CrossRef]

126. He, K.; Zheng, B.; Kim, C.H.; Rogers, L.; Zheng, Q. Direct analysis and identification of triterpene glycosides

by LC/MS in black cohosh, Cimicifuga racemosa, and in several commercially available black cohosh products.

Planta Med. 2000, 66, 635–640. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

127. Bedir, E.; Khan, I.A. Cimiracemoside A: A new cyclolanostanol xyloside from the rhizome of Cimicifuga

racemosa. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2000, 48, 425–427. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

128. Lai, G.F.; Wang, Y.-F.; Fan, L.-M.; Cao, J.-X.; Luo, S.-D. Triterpenoid glycoside from Cimicifuga racemosa. J.

Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2005, 7, 695–699. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

129. Shao, Y.; Harris, A.; Wang, M.; Zhang, H.; Cordell, G.A.; Bowman, M.; Lemmo, E. Triterpene glycosides from

Cimicifuga racemosa. J. Nat. Prod. 2000, 63, 905–910. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

130. Watanabe, K.; Mimaki, Y.; Sakagami, H.; Sashida, Y. Cycloartane glycosides from the rhizomes of Cimicifuga

racemosa and their cytotoxic activities. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2002, 50, 121–125. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

131. Tsukamoto, S.; Aburatani, M.; Ohta, T. Isolation of CYP3A4 inhibitors from the black cohosh (Cimicifuga

racemosa). Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2005, 2, 223–226. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

132. Cicek, S.S.; Schwaiger, S.; Ellmerer, E.P.; Stuppner, H. Development of a fast and convenient method for the

isolation of triterpene saponins from Actaea racemosa by high-speed countercurrent chromatography coupled

with evaporative light scattering detection. Planta Med. 2010, 76, 467–473. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

133. Jamróz, M.K.; Jamróz, M.H.; Dobrowolski, J.C.; Gli´nski, J.A.; Davey, M.H.; Wawer, I. Novel and unusual

triterpene from black cohosh. Determination of structure of 9,10-seco-9,19-cyclolanostane xyloside

(cimipodocarpaside) by NMR, IR and Raman spectroscopy and DFT calculations. Spectrochim. Acta Part A

Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2011, 78, 107–112. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

134. Jamróz, M.K.; Paradowska, K.; Gli´nski, J.A.; Wawer, I. 13C CPMAS NMR studies and DFT calculations of

triterpene xylosides isolated from Actaea racemosa. J. Mol. Struct. 2011, 994, 248–255. [CrossRef]

135. Jamróz, M.K.; Jamróz, M.H.; Dobrowolski, J.C.; Gli´nski, J.A.; Gle´nsk, M. One new and six known triterpene

xylosides from Cimicifuga racemosa: FT-IR, Raman and NMR studies and DFT calculations. Spectrochim. Acta

Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2012, 93, 10–18. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

136. He, C.-C.; Dai, Y.-Q.; Hui, R.-R.; Hua, J.; Chen, H.-J.; Luo, Q.-Y.; Li, J.-X. NMR-based metabonomic approach

on the toxicological effects of a Cimicifuga triterpenoid. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2012, 32, 88–97. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

137. Kruse, S.O.; Löhning, A.; Pauli, G.F.; Winterhoff, H.; Nahrstedt, A. Fukiic and piscidic acid esters from the

rhizome of Cimicifuga racemosa and the in vitro estrogenic activity of fukinolic acid. Planta Med. 1999, 65,

763–764. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

138. Stromeier, S.; Petereit, F.; Nahrstedt, A. Phenolic esters from the rhizomes of Cimicifuga racemosa do not cause

proliferation effects in MCF-7 cells. Planta Med. 2005, 71, 495–500. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

139. Chen, S.-N.; Fabricant, D.S.; Lu, Z.-Z.; Zhang, H.; Fong, H.H.S.; Farnsworth, N.R. Cimiracemates A-D,

phenylpropanoid esters from the rhizomes of Cimicifuga racemosa. Phytochemistry 2002, 61, 409–413.

[CrossRef]

140. Li, W.; Chen, S.; Fabricant, D.; Angerhofer, C.K.; Fong, H.S.; Farnsworth, N.R.; Fitzloff, J.F. High-performance

liquid chromatographic analysis of black cohosh (Cimicifuga racemosa) constituents with in-line evaporative

light scattering and photodiode array detection. Anal. Chim. Acta 2002, 471, 61–75. [CrossRef]

141. Nuntanakorn, P.; Jiang, B.; Einbond, L.S.; Yang, H.; Kronenberg, F.; Weinstein, I.B.; Kennelly, E.J. Polyphenolic

constituents of Actaea racemosa. Nournal Nat. Prod. 2006, 69, 314–318. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

142. Gödecke, T.; Lankin, D.C.; Nikolic, D.; Chen, S.-N.; van Breemen, R.B.; Farnsworth, N.R.; Pauli, G.F.

Guanidine alkaloids and Pictet-Spengler adducts from black cohosh (Cimicifuga racemosa). J. Nat. Prod. 2009,

72, 433–437. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

143. Azimova, S.S.; Gluchenkova, A.I. (Eds.) Collinsonia canadensis L. In Lipids, Lipophilic Components and Essential

Oils from Plant Sources; Springer: London, UK, 2012; p. 401.

144. Joshi, B.S.; Moore, K.M.; Pelletier, S.W.; Puar, M.S.; Pramanik, B.N. Saponins from Collinsonia canadensis. J.

Nat. Prod. 1992, 55, 1468–1474. [CrossRef]

145. Stevens, J.F.; Ivancic, M.; Deinzer, M.L.; Wollenweber, E. A novel 2-hydroxyflavanone from Collinsonia

canadensis. J. Nat. Prod. 1999, 62, 392–394. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

146. Hutton, K. A Comparative Study of the Plants Used for Medicinal Purposes by the Creek and Seminole

Tribes. Master’s Thesis, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA, 2010.

147. Mukhtar, N.; Iqbal, K.; Anis, I.; Malik, A. Sphingolipids from Conyza canadensis. Phytochemistry 2002, 61,

1005–1008. [CrossRef]

148. Mukhtar, N.; Iqbal, K.; Malik, A. Sphingolipids from Conyza canadensis. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2002, 50,

1558–1560. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

149. Yan, M.M.; Li, T.Y.; Zhao, D.Q.; Shao, S.; Bi, S.N. A new derivative of triterpene with anti-melanoma B16

activity from Conyza canadensis. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2010, 21, 834–837. [CrossRef]

150. Shakirullah, M.; Ahmad, H.; Shah, M.R.; Imtiaz, A.; Ishaq, M.; Khan, N.; Badshah, A.; Khan, I. Antimicrobial

activities of conyzolide and conyzoflavone from Conyza canadensis. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2011, 26,

468–471. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

151. Xie, W.D.; Gao, X.; Jia, Z.J. A new C-10 acetylene and a new triterpenoid from Conyza canadensis. Arch. Pharm.

Res. 2007, 30, 547–551. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

152. Ding, Y.; Su, Y.; Guo, H.; Yang, F.; Mao, H.; Gao, X.; Zhu, Z.; Tu, G. Phenylpropanoyl esters from horseweed

(Conyza canadensis) and their inhibitory effects on catecholamine secretion. J. Nat. Prod. 2010, 73, 270–274.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

153. Queiroz, S.C.N.; Cantrell, C.L.; Duke, S.O.; Nandula, V.; Moraes, R.M.; Cerdeira, A.L. Bioassay-directed

isolation and identification of phytotoxic terpenoids from horseweed (Conyza canadensis). Planta Med. 2012,

78, P48. [CrossRef]

154. Porto, R.S.; Rath, S.; Queiroz, S.C.N. Conyza canadensis: Green extraction method of bioactive compounds

and evaluation of their antifungal activity. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2017, 28, 913–919. [CrossRef]

155. Pawlaczyk, I.; Czerchawski, L.; Kuliczkowski, W.; Karolko, B.; Pilecki, W.; Witkiewicz, W.; Gancarz, R.

Anticoagulant and anti-platelet activity of polyphenolic-polysaccharide preparation isolated from the

medicinal plant Erigeron canadensis L. Thromb. Res. 2011, 127, 328–340. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

156. Csupor-Löffler, B.; Hajdú, Z.; Zupkó, I.; Molnár, J.; Forgo, P.; Kele, Z.; Hohmann, J. New dihydropyrone

derivatives and further antitumor compounds from Conyza canadensis. Planta Med. 2010, 76, P258. [CrossRef]

157. Csupor-Löffler, B.; Hajdú, Z.; Zupkó, I.; Molnár, J.; Forgo, P.; Vasas, A.; Kele, Z.; Hohmann, J. Antiproliferative

constituents of the roots of Conyza canadensis. Planta Med. 2011, 77, 1183–1188. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

158. Liu, K.; Qin, Y.-H.; Yu, J.-Y.; Ma, H.; Song, X.-L. 3-β-Erythrodiol isolated from Conyza canadensis inhibits

MKN-45 human gastric cancer cell proliferation by inducing apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, DNA fragmentation,

ROS generation and reduces tumor weight and volume in mouse xenograft model. Oncol. Rep. 2016, 35,

2328–2338. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

159. Banday, J.A.; Mir, F.A.; Farooq, S.; Qurishi, M.A.; Koul, S.; Razdan, T.K. Salicylic acid and methyl gallate

from the roots of Conyza canedensis. Int. J. Chem. Anal. Sci. 2012, 3, 2–5.

160. Banday, J.A.; Farooq, S.; Qurishi, M.A.; Koul, S.; Razdan, T.K. Conyzagenin-A and B, two new epimeric

lanostane triterpenoids from Conyza canadensis. Nat. Prod. Res. 2013, 27, 975–981. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

161. Curini, M.; Bianchi, A.; Epifano, F.; Bruni, R.; Torta, L.; Zambonelli, A. Compsotion and in vitro antifungal

activity of essential oils of Erigeron canadensis and Myrtus communis from France. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2003, 39,

191–194. [CrossRef]

162. Lis, A.; Piggott, J.R.; Góra, J. Chemical composition variability of the essential oil of Conyza canadensis Cronq.

Flavour Fragr. J. 2003, 18, 364–367. [CrossRef]

163. Tzakou, O.; Vagias, C.; Gani, A.; Yannitsaros, A. Volatile constituents of essential oils isolated at different

growth stages from three Conyza species growing in Greece. Flavour Fragr. J. 2005, 20, 425–428. [CrossRef]

164. Lis, A.; Góra, J. Essential oil of Conyza canadensis (L.) Cronq. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2000, 12, 781–783. [CrossRef]

165. Stoyanova, A.; Georgiev, E.; Kermedchieva, D.; Lis, A.; Gora, J. Changes in the essential oil of Conyza

canadensis (L.) Cronquist. during its vegetation. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2003, 15, 44–45. [CrossRef]

166. Rustaiyan, A.; Azar, P.A.; Moradalizadeh, M.; Masoudi, S.; Ameri, N. Volatile constituents of three

Compositae herbs: Anthemis altissima L. var altissima, Conyza canadensis (L.) Cronq. and Grantina aucheri

Boiss. growing wild in Iran. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2004, 16, 579–581. [CrossRef]

167. Miyazawa, M.; Yamamoto, K.; Kameoka, H. The essential oil of Erigeron canadensis L. J. Essent. Oil Res. 1992,

4, 227–230. [CrossRef]

168. Choi, H.-J.; Want, H.-Y.; Kim, Y.-N.; Heo, S.-J.; Kim, N.-K.; Jeong, M.-S.; Park, Y.-H.; Kim, S. Composition and

cytotoxicity of essential oil extracted by steam distillation from horseweed (Erigeron canadensis L.) in Korea. J.

Korean Soc. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2008, 51, 55–59.

169. Veres, K.; Csupor-Löffler, B.; Lázár, A.; Hohmann, J. Antifungal activity and composition of essential oils of

Conyza canadensis herbs and roots. Sci. World J. 2012, 2012. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

170. Liu, Y.; Du, D.; Liang, Y.; Xin, G.; Huang, B.-Z.; Huang, W. Novel polyacetylenes from Coreopsis tinctoria Nutt.

J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2015, 17, 744–749. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

171. Lam, S.-C.; Lam, S.-F.; Zhao, J.; Li, S.-P. Rapid identification and comparison of compounds with antioxidant

activity in Coreopsis tinctoria herbal tea by high-performance thin-layer chromatography coupled with DPPH

bioautography and densitometry. J. Food Sci. 2016, 81, C2218–C2223. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

172. Zhang, Y.; Shi, S.; Zhao, M.; Chai, X.; Tu, P. Coreosides A-D, C14-polyacetylene glycosides from the capitula

of Coreopsis tinctoria and its anti-inflammatory activity against COX-2. Fitoterapia 2013, 87, 93–97. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

173. Guo, J.; Wang, A.; Yang, K.; Ding, H.; Hu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Huang, S.; Xu, J.; Liu, T.; Yang, H.; et al. Isolation,

characterization and antimicrobial activities of polyacetylene glycosides from Coreopsis tinctoria Nutt.

Phytochemistry 2017, 136, 65–69. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

174. Du, D.; Jin, T.; Xing, Z.-H.; Hu, L.-Q.; Long, D.; Li, S.-F.; Gong, M. One new linear C14 polyacetylene glucoside

with antiadipogenic activities on 3T3-L1 cells from the capitula of Coreopsis tinctoria. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res.

2016, 18, 784–790. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

175. Dias, T.; Liu, B.; Jones, P.; Houghton, P.J.; Mota-Filipe, H.; Paulo, A. Cytoprotective effect of Coreopsis tinctoria

extracts and flavonoids on tBHP and cytokine-induced cell injury in pancreatic MIN6 cells. J. Ethnopharmacol.

2012, 139, 485–492. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

176. Zhang, Y.; Shi, S.; Zhao, M.; Jiang, Y.; Tu, P. A novel chalcone from Coreopsis tinctoria Nutt. Biochem. Syst. Ecol.

2006, 34, 766–769. [CrossRef]

177. Dias, T.; Bronze, M.R.; Houghton, P.J.; Mota-Filipe, H.; Paulo, A. The flavonoid-rich fraction of Coreopsis

tinctoria promotes glucose tolerance regain through pancreatic function recovery in streptozotocin-induced

glucose-intolerant rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 132, 483–490. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

178. Abdureyim, A.; Abliz, M.; Sultan, A.; Eshbakova, K.A. Phenolic compounds from the flowers of Coreopsis

tinctoria. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2013, 48, 1085–1086. [CrossRef]

179. Ma, Z.; Zheng, S.; Han, H.; Meng, J.; Yang, X.; Zeng, S.; Zhou, H.; Jiang, H. The bioactive components of

Coreopsis tinctoria (Asteraceae) capitula: Antioxidant activity in vitro and profile in rat plasma. J. Funct. Foods

2016, 20, 575–586. [CrossRef]

180. Chen, L.X.; Hu, D.J.; Lam, S.C.; Ge, L.; Wu, D.; Zhao, J.; Long, Z.R.; Yang, W.J.; Fan, B.; Li, S.P.

Comparison of antioxidant activities of different parts from snow chrysanthemum (Coreopsis tinctoria

Nutt.) and identification of their natural antioxidants using high performance liquid chromatography

coupled with diode array detection and mass spectrometry and 2,20-azinobis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-sulfonic

acid)diammonium salt-based assay. J. Chromatogr. A 2016, 1428, 134–142. [PubMed]

181. Deng, Y.; Lam, S.-C.; Zhao, J.; Li, S.-P. Quantitative analysis of flavonoids and phenolic acid in Coreopsis

tinctoria Nutt. by capillary zone electrophoresis. Electrophoresis 2017, 38, 2654–2661. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

182. Yang, Y.; Sun, X.; Liu, J.; Kang, L.; Chen, S.; Ma, B.; Guo, B. Quantitative and qualitative analysis of

flavonoids and phenolic acids in snow chrysanthemum (Coreopsis tinctoria Nutt.) by HPLC-DAD and

UPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS. Molecules 2016, 21, 1307. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

183. Zalaru, C.; Cri¸san, C.C.; C ˇ alinescu, I.; Moldovan, Z.; ¸T ˇ ârcomnicu, I.; Litescu, S.C.; Tatia, R.; Moldovan, L.;

Boda, D.; Iovu, M. Polyphenols in Coreopsis tinctoria Nutt. fruits and the plant extracts antioxidant capacity

evaluation. Cent. Eur. J. Chem. 2014, 12, 858–867. [CrossRef]

184. Wang, T.; Xi, M.; Guo, Q.; Wang, L.; Shen, Z. Chemical components and antioxidant activity of volatile oil of

a Compositae tea (Coreopsis tinctoria Nutt.) from Mt. Kunlun. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 67, 318–323. [CrossRef]

185. Hostettmann, K.; Hostettmann-Kaldas, M.; Nakanishi, K. Molluscicidal saponins from Cornus florida L. Helv.

Chim. Acta 1978, 61, 1990–1995. [CrossRef]

186. Robins, R.J.; Abraham, T.W.; Parr, A.J.; Eagles, J.; Walton, N.J. The biosynthesis of tropane alkaloids in Datura

stramonium: The identity of the intermediates between N-methylpyrrolinium salt and tropinone. J. Am.

Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 10929–10934. [CrossRef]

187. Monforte-González, M.; Ayora-Talavera, T.; Maldonado-Mendoza, E.; Loyola-Vargas, V.M. Quantitative

analysis of serpentine and ajmalicine in plant tissues of Catharanthus roseus and hyoscyamine

and scopolamine in root tissues of Datura stramonium by thin layer chromatography-densitometry.

Phytochem. Anal. 1992, 3, 117–121. [CrossRef]

188. Lanfranchi, D.A.; Tomi, F.; Casanova, J. Enantiomeric differentiation of atropine/hyoscyamine by 13C NMR

spectroscopy and its application to Datura stramonium extract. Phytochem. Anal. 2010, 21, 597–601. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

189. Mroczek, T.; Głowniak, K.; Kowalska, J. Solid-liquid extraction and cation-exchange solid-phase extraction

using a mixed-mode polymeric sorbent of Datura and related alkaloids. J. Chromatogr. A 2006, 1107, 9–18.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

190. Fallas, A.L.; Thomson, R.H. Ebenaceae extractives. Part III. Binaphthaquinones from Diospyros species. J.

Chem. Soc. C Org. 1968, 1968, 2279–2282. [CrossRef]

191. Rashed, K.; Ciri´c, A.; Glamoˇclija, J.; Sokovi´c, M. Antibacterial and antifungal activities of methanol extract ´

and phenolic compounds from Diospyros virginiana L. Ind. Crops Prod. 2014, 59, 210–215. [CrossRef]

192. Wang, X.; Habib, E.; León, F.; Radwan, M.M.; Tabanca, N.; Gao, J.; Wedge, D.E.; Cutler, S.J. Antifungal

metabolites from the roots of Diospyros virginiana by overpressure layer chromatography. Chem. Biodivers.

2011, 8, 2331–2340. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

193. Kiss, A.; Kowalski, J.; Melzig, M.F. Compounds from Epilobium angustifolium inhibit the specific

metallopeptidases ACE, NEP and APN. Planta Med. 2004, 70, 919–923. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

194. Kiss, A.; Kowalski, J.; Melzig, M.F. Effect of Epilobium angustifolium L. extracts and polyphenols on cell

proliferation and neutral endopeptidase activity in selected cell lines. Pharmazie 2006, 61, 66–69. [PubMed]

195. Ramstead, A.G.; Schepetkin, I.A.; Quinn, M.T.; Jutila, M.A. Oenothein B, a cyclic dimeric ellagitannin

isolated from Epilobium angustifolium, enhances IFNγ production by lymphocytes. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e50546.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

196. Baert, N.; Karonen, M.; Salminen, J.P. Isolation, characterisation and quantification of the main oligomeric

macrocyclic ellagitannins in Epilobium angustifolium by ultra-high performance chromatography with diode

array detection and electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2015, 1419, 26–36. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

197. Baert, N.; Kim, J.; Karonen, M.; Salminen, J.P. Inter-population and inter-organ distribution of the main

polyphenolic compounds of Epilobium angustifolium. Phytochemistry 2017, 134, 54–63. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

198. Park, B.-J.; Tomohiko, M. Feruloyl, caffeoyl, and flavonol glucosides from Equisetum hyemale. Chem. Nat.

Compd. 2011, 47, 363–365. [CrossRef]

199. Jin, M.; Zhang, C.; Zheng, T.; Yao, D.; Shen, L.; Luo, J.; Jiang, Z.; Ma, J.; Jin, X.-J.; Cui, J.; et al. A new

phenyl glycoside from the aerial parts of Equisetum hyemale. Nat. Prod. Res. 2014, 28, 1813–1818. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

200. Price, J.I. An in vitro evaluation of the Native American ethnomedicinal plant Eryngium yuccifolium as a

treatment for snakebite envenomation. J. Intercult. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 5, 219–225. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

201. Yarnell, E.; Abascal, K. Natural approaches to treating chronic prostatitis and chronic pelvic pain syndromes.

Altern. Complement. Ther. 2005, 11, 246–251. [CrossRef]

202. Ayoub, N.; Al-Azizi, M.; König, W.; Kubeczka, K.H. Essential oils and a novel polyacetylene from Eryngium

yuccifolium Michaux. (Apiaceae). Flavour Fragr. J. 2006, 21, 864–868. [CrossRef]

203. Zhang, Z.; Li, S.; Ownby, S.; Wang, P.; Yuan, W.; Zhang, W.; Beasley, R.S. Phenolic compounds and rare

polyhydroxylated triterpenoid saponins from Eryngium yuccifolium. Phytochemistry 2008, 69, 2070–2080.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

204. Wang, P.; Yuan, W.; Deng, G.; Su, Z.; Li, S. Triterpenoid saponins from Eryngium yuccifolium “Kershaw Blue”.

Phytochem. Lett. 2013, 6, 306–309. [CrossRef]

205. Wang, P.; Su, Z.; Yuan, W.; Deng, G.; Li, S. Phytochemical constituents and pharmacological activities of

Eryngium L. (Apiaceae). Pharm. Crop. 2012, 3, 99–120. [CrossRef]

206. Cavallito, C.J.; Haskell, T.H. α-Methylene butyrolactone from Erythronium americanum. J. Am. Chem. Soc.

1946, 68, 2332–2334. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

207. Tsuda, Y.; Marion, L. The alkaloids of Eupatorium maculatum L. Can. J. Chem. 1963, 41, 1919–1924. [CrossRef]

208. Wiedenfeld, H.; Hösch, G.; Roeder, E.; Dingermann, T. Lycopsamine and cumambrin B from Eupatorium

maculatum. Pharmazie 2009, 64, 415–416. [PubMed]

209. Maas, M.; Hensel, A.; Da Costa, F.B.; Brun, R.; Kaiser, M.; Schmidt, T.J. An unusual dimeric guaianolide with

antiprotozoal activity and further sesquiterpene lactones from Eupatorium perfoliatum. Phytochemistry 2011,

72, 635–644. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

210. Herz, W.; Kalyanaraman, P.S.; Ramakrishnan, G.; Blount, J.F. Sesquiterpene lactones of Eupatorium perfoliatum.

J. Org. Chem. 1977, 42, 2264–2271. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

211. Habtemariam, S. Activity-guided isolation and identification of free radical-scavenging components from

ethanolic extract of boneset (leaves of Eupatorium perfoliatum). Nat. Prod. Commun. 2008, 3, 1317–1320.

212. Maas, M.; Deters, A.M.; Hensel, A. Anti-inflammatory activity of Eupatorium perfoliatum L. extracts, eupafolin,

and dimeric guaianolide via iNOS inhibitory activity and modulation of inflammation-related cytokines and

chemokines. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 137, 371–381. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

213. Maas, M.; Petereit, F.; Hensel, A. Caffeic acid derivatives from Eupatorium perfoliatum L. Molecules 2009, 14,

36–45. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

214. Herz, W. Chemistry of the Eupatoriinae. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2001, 29, 1115–1137. [CrossRef]

215. Hensel, A.; Maas, M.; Sendker, J.; Lechtenberg, M.; Petereit, F.; Deters, A.; Schmidt, T.; Stark, T. Eupatorium

perfoliatum L.: Phytochemistry, traditional use and current applications. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 138, 641–651.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

216. Lewis, N.G.; Inciong, M.E.J.; Ohashi, H.; Towers, G.H.N.; Yamamoto, E. Exclusive accumulation of Z-isomers

of monolignols and their glucosides in bark of Fagus grandifolia. Phytochemistry 1988, 27, 2119–2121.

[CrossRef]

217. Stout, G.H.; Balkenhol, W.J. Xanthones of the Gentianaceae-I: Frasera caroliniensis. Tetrahedron 1969, 25,

1947–1960. [CrossRef]

218. Aberham, A.; Pieri, V.; Croom, E.M.; Ellmerer, E.; Stuppner, H. Analysis of iridoids, secoiridoids and

xanthones in Centaurium erythraea, Frasera caroliniensis and Gentiana lutea using LC-MS and RP-HPLC. J.

Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2011, 54, 517–525. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

219. Eyles, A.; Jones, W.; Riedl, K.; Cipollini, D.; Schwartz, S.; Chan, K.; Herms, D.A.; Bonello, P. Comparative

phloem chemistry of Manchurian (Fraxinus mandshurica) and two North American ash species (Fraxinus

americana and Fraxinus pennsylvanica). J. Chem. Ecol. 2007, 33, 1430–1448. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

220. Takenaka, Y.; Tanahashi, T.; Shintaku, M.; Sakai, T.; Nagakura, N. Parida Secoiridoid glucosides from Fraxinus

americana. Phytochemistry 2000, 55, 275–284. [CrossRef]

221. Aybek, A.; Zhou, J.; Malik, A.; Umar, S.; Xiao, Z. Catechins and proanthocyanidins from seeds of Fraxinus

americana. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2015, 51, 565–567. [CrossRef]

222. Gallardo, A.; Picollo, M.I.; González-Audino, P.; Mougabure-Cueto, G. Insecticidal activity of individual and

mixed monoterpenoids of Geranium essential oil against Pediculus humanus capitis (Phthiraptera: Pediculidae).

J. Med. Entomol. 2012, 49, 332–335. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

223. Sánchez-Tena, S.; Fernández-Cachón, M.L.; Carreras, A.; Mateos-Martín, M.L.; Costoya, N.; Moyer, M.P.;

Nuñez, M.J.; Torres, J.L.; Cascante, M. Hamamelitannin from witch hazel (Hamamelis virginiana) displays

specific cytotoxic activity against colon cancer cells. J. Nat. Prod. 2012, 75, 26–33. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

224. Duckstein, S.M.; Stintzing, F.C. Investigation on the phenolic constituents in Hamamelis virginiana leaves by

HPLC-DAD and LC-MS/MS. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2011, 401, 677–688. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

225. Dauer, A.; Rimpler, H.; Hensel, A. Polymeric proanthocyanidins from the bark of Hamamelis virginiana. Planta

Med. 2003, 69, 89–91. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

226. Touriño, S.; Lizárraga, D.; Carreras, A.; Lorenzo, S.; Ugartondo, V.; Mitjans, M.; Vinardell, M.P.; Julía, L.;

Cascante, M.; Torres, J.L. Highly galloylated tannin fractions from witch hazel (Hamamelis virginiana) bark:

Electron transfer capacity, in vitro antioxidant activity, and effects on skin-related cells. Chem. Res. Toxicol.

2008, 21, 696–704. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

227. Hartisch, C.; Kolodziej, H. Galloylhamameloses and proanthocyanidins from Hamamelis virginiana.

Phytochemistry 1996, 42, 191–198. [CrossRef]

228. Lucas, R.A.; Smith, R.G.; Dorfman, L. The isolation of dihydromexicanin E from Helenium autumnale L. J.

Org. Chem. 1964, 29, 2101. [CrossRef]

229. Herz, W.; Subramaniam, P.S.; Dennis, N. Constituents of Helenium species. XXIII. Stereochemistry of flexuosin

A and related compounds. J. Org. Chem. 1969, 34, 2915–2917. [CrossRef]

230. Herz, W.; de Vivar, A.R.; Romo, J.; Viswanathan, N. Constituents of Helenium species. XIII. The structure of

helenalin and mexicanin A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1963, 85, 19–26. [CrossRef]

231. Herz, W.; Subramaniam, P.S. Pseudoguianolides in Helenium autumnale from Pennsylvania. Phytochemistry

1972, 11, 1101–1103. [CrossRef]

232. Lee, K.-H.; Meck, R.; Piantadosi, C.; Huang, E.-S. Antitumor agents. 4. Cytotoxicity and in vivo activity of

helenalin esters and related derivatives. J. Med. Chem. 1973, 16, 299–301. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

233. Furukawa, H.; Lee, K.-H.; Shingu, T.; Meck, R.; Piantadosi, C. Carolenin and carolenalin, two new

guaianolides in Helenium autumnale L. from North Carolina. J. Org. Chem. 1973, 38, 1722–1725. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]